Most professional advisors develop certain habits and ways of working, over time, that become inviolate components of professional practice as automatic processes in their service delivery.

Standardised services become commoditised services. Commoditised services are easily duplicated, rapidly devalued, readily purloined, and ultimately replaced by clients always looking for quicker, cheaper, more accessible solutions.

The practices in question may be based on outdated or ineffective thinking, old and defunct technologies, or conservative and/or risk averse corporate cultures. Or an adviser may simply have become too comfortable doing things a certain way – just because that’s the way they’ve always done it, or because that’s the way everyone else around them seems to do it.

By their nature, habits are sticky and tricky things. Every habit starts with creation of a 3-part psychological pattern called a “habit loop” (The Power of Habit – Charles Duhigg).

Part #1 is the “trigger” – a cue that tells the brain to go into automatic mode: critical thinking is turned off to allow the behaviour to proceed, unmolested, to “do its thing”.

Part #2 is the “routine” – the actual (habitual) behaviour, itself. This what we focus on when we think about habits.

Part #3 is the “reward” – something the brain receives, and interprets favourably, as a result of performing the routine. The reward helps the brain to recognise, like, and remember the particular habit loop, which encourages its future selection and use.

Neuroscience place habit-making behaviours in part of the brain called the basal ganglia, which is also active in the development of emotions, memories, and pattern recognition.

Meanwhile, critical thinking and decision-making take place in a different part of the brain – the prefrontal cortex.

Once a behaviour becomes automatic and is being driven by the basal ganglia the brain “accepts” that that action is under control and, like a parent with a small child placed in a safe environment, turns its attention to other, more pressing things.

This is an example of a complex, evolutionary, survival-related process where, to avoid getting itself overheated and fried, our brains constantly focus on and select only the stuff that needs our priority attention at a given time, rather than trying to process everything, everywhere, all the time.

Proof: you suspend awareness of the weather, sights, smells, and people around you when you need to cross a busy street. For a short time, you focus only on the traffic that could kill you. As soon as you’ve crossed safely, you switch back on to the sights and sounds.

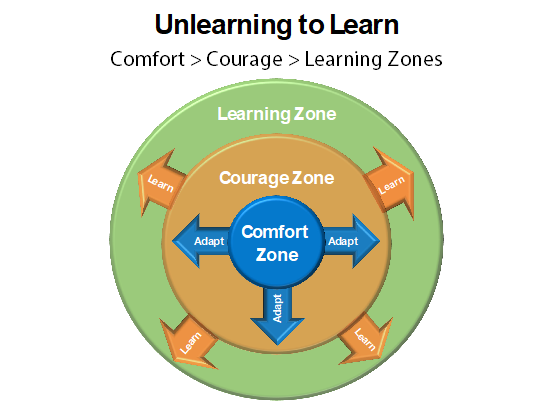

To learn new ways of working, we need to “unlearn” our old habits so we can become open to new ideas, techniques, and approaches, and be willing to learn new skills to help us wield new tools.

Change is usually perceived and experienced as a challenging process. Most humans fear change, and don’t welcome it, unless they feel strongly motivated by a greater fear of the consequences of not changing, or by the prospects of large rewards sufficient to stimulate blind greed, or overcome natural caution, or congenital laziness!

Fear of change is deep-rooted in our psyches. Moving out into the unknown feels unsafe because, by definition, we can’t control what we don’t know and understand – and for the vast majority of human evolution, the outside world was hostile and dangerous. It’s only in comparatively recent times we’ve been able to feel safe stepping outside our caves without the backing of the tribe, and weapons.

To welcome change is to be willing to let go of what’s familiar – expecting to improve processes, and/or outcomes by doing something differently.

In professional terms, that translates into being willing and able to adapt to new clients, markets, technologies, and services, and to invest in overcoming resource constraints and other challenges.

We do all these things to maintain and stimulate our own interest in our professional work, to remain relevant in our professional lives, and to sustain our commercial competitiveness in the markets we inhabit.

Unlearning old habits to make headspace for new knowledge and skills, and new services for existing and prospective new clients, ultimately leads to better outcomes for advisers, staff, clients, and the industries / sectors in which they all operate.